The 49% plunge in the Turkish Lira against the US Dollar over the past year may be all over the news, but it is far from alone. The Argentinian Peso has slumped 41%, the Brazilian Real 17%, the Russian Rubel 12% and the Venezuelan Bolivar has collapsed 100% as its Government slashed 5 zeros off its currency last month. In contrast, South African Rand investors have been relatively unscathed, falling only 8% over the same period.

These currencies are both significant and relevant – according to IMF’s 2017 World Economic Outlook Database, Brazil’s economy was nearly 6 times larger than South Africa’s, Turkey was 2.4x the size, Argentina, 1.8x and only Venezuela was smaller but with a currency worth zero, that’s hardly comforting.

The Economist launched the Big Mac Index in 1986, which compares the price of a Big Mac globally in an informal attempt to measure the purchasing power parity of currencies. But these days you can get itemised, crowd sourced data on the cost of living in various cities / countries from the website, Numbeo, where you can see for example that rental prices in Istanbul are 43% lower than Pretoria or that restaurant prices in Ho Chi Minh City are 55% lower than in Cape Town.

These purchasing power parity methods are both interesting but I think it may be more useful to think of a currency as a country’s share price – share prices rise when the market feels confident that prospects are improving, and they fall when growth prospects are declining or the market loses faith in management. So too with currencies, only in place of “management” read “Government.”

If so, then the formula for value destruction for both share prices and currencies applies equally – if management/Government act in their own best interests and against those of shareholders/stakeholders (population & investors) then the share price/currency will fall. I think it’s that simple.

The US dollar is currently strong because economic conditions are good – the country has low unemployment and is enjoying strong GDP growth. Sterling on the other hand is weak because economic conditions are deteriorating – retail sales are weak, house prices are falling, there is uncertainty over Brexit and the market is losing faith in the Government.

Global investors today have a choice of approximately 70 countries that are ranked investment grade so unless Governments respect property rights and act in a way that protects investor interests, they will invest elsewhere. And the cost to the economy of them doing so is high – capital flight leads to currencies falling, driving higher inflation which causes Central Banks to raise interest rates and this higher cost of borrowing often results in a collapse in the local economy. Once currencies collapse, they rarely recover.

Venezuela has more barrels of oil reserves than Saudi Arabia, yet despite a $70 oil price, the country is bankrupt, arguably largely because in 2007 the Government disregarded property rights and tried to change the contract terms with large global oil majors. Exxon, ConocoPhilips and Petro-Canada walked away from their investments in the country, taking with them their oil extraction technologies necessary for extracting Venezuela’s heavy crude. This, together with alleged corruption at state oil firm PDVSA, the country’s only foreign currency generator, has left the supermarket shelves bare, the medicine cabinets empty and the population destitute.

Russia is a country with some of the smartest people on the planet, a rich history and extensive natural resources yet many foreign investors steer clear of it because of fears of corruption and concerns that the rule of law will not be upheld. In 2003, the Government undermined property rights by seizing Yukos’s key oilfields, and in 2014 its annexation of the Crimean peninsula for political gain, unleashed global sanctions and raised the cost of capital, to the financial detriment of its citizens. Today, Gazprom, the Russian oil giant, holds 17% of the world’s natural gas reserves and is expected to earn $17bn of net income this year, yet it has a market value of only $53bn, less than Activision, the US video game company that produces “Call of Duty” and which is expected to earn less than 10% of Gazprom’s earnings.

In Turkey, President Erdogan acted in his own self-interest on the 10th of July by naming his son-in-law as the new finance minister causing the Turkish Lira to fall 11%. This simple act of nepotism increased the cost of borrowing for the entire nation with the 10 year Government bonds now yielding 19%.

And in Zimbabwe, the disregard of property rights over the years together, with the corruption that followed, has so destroyed the economy that one of its largest banks today, Barclays Zimbabwe, has shareholder equity of only $75m (Barclays UK has shareholder equity of $83bn)

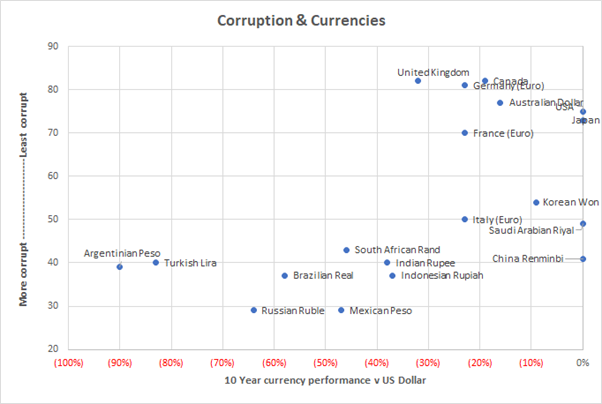

Using Bloomberg data, I analysed the performance of the currencies of the G20 countries over the past 10 years and compared them to their Corruption Index scores compiled by Transparency International (www.transparency.org) (0 = highly corrupt, 100 = very clean)

Ignoring the currencies pegged to the USD, what the chart below shows, is that the best performing currencies relative to the USD were generally those of the least corrupt countries (corruption Score of 70 or more) and the worst performing currencies were those of the most corrupt countries with a corruption score less than 50.

Source: Bloomberg, Transparency International, Ranmore Fund Management

This may be no coincidence and in fact makes economic sense because corruption and mismanagement raise prices and higher prices dampen economic growth – if Eskom had not been mis-managed over the past 10 years by allegedly buying coal from related parties at inflated prices, electricity prices wouldn’t have tripled and consumers would have had more money left over at the end of each month to spend at restaurants and in shops, thereby driving economic growth. South Africa’s economic growth over the past 10 years has only averaged 1.6%, half the rate of the USA’s 3.2%

For Governments, the economic lessons in this simple analysis are:

- Be firm on corruption because corruption raises prices, leading to lower economic growth and a declining currency,

- A weak currency for an oil importing & food exporting nation increases fuel and food prices, impoverishing the local population and dampening economic growth even further,

- Treat international investors carefully ensuring that unlike: Russia, Venezuela and Zimbabwe, property rights are always protected. Investors have lots of choice these days.

Investors should always consider professional advice from their advisors before allocating their capital, but perhaps this analysis suggests that the safest way to preserve wealth is to ensure that the bulk of your investable assets are denominated in a basket of strong currencies in countries with low levels of mismanagement and alleged corruption.

Sean Peche is the portfolio manager of the Ranmore Global Equity Fund